19 World Helicopter Records Captured – Jack Schweibold

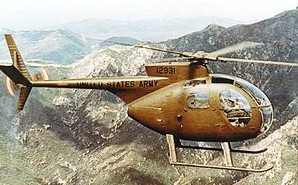

That is what the headlines said forty-five years ago. The Army, Hughes Aircraft and Allison Engines battled the skies during a thirty day period sanctioned by the National Aeronautics Association and the Federation Aeronautic International. Howard Hughes had just won the Army’s Light Observation (LOH) competition (see previous 4 PJA articles) and funded this attack on the World Record Books with his winning OH-6 (Hughes Model 369) helicopter. The following describes in detail our winning two distance records that still stand today:

Hunting For Helicopter Records

Get Your License

“Jack, the Army and Hughes both called and they have asked you to go hunting!” our Program Manager phones.

“Huh,” I gulp, “The last time I went hunting with the military . . . they bagged ME, for six years! What are you talking about?”

“No,” he replies. “Hughes just received permission from the Army to use one of their prototypes for a month, to break as many Aviation World Records as possible. Hughes will fund the operation and the Army will support it out of their Test Detachment at Edwards AFB. We will provide technical support on the engine . . . and the Army and Hughes have offered you a seat for the distance record.”

I’m flabbergasted. I haven’t even heard about this in the rumor mill. “Well . . . I guess so-o,” I stammer.

“We don’t know much about it ourselves yet,” he continues, “apparently, it’s something Hughes Sales and Engineering Departments dreamed up, and while it’s against government policy, the Army says Okay. They must need a shot in the arm, too. Everyone feels you should be on the team. Someone will be contacting you regarding a Sporting License needed from the Federation Aeronautic International (FAI) in Paris. You are cleared to do whatever is necessary to represent Allison.”

Shortly after this conversation, Bob Ferry, Hughes Chief Pilot and Phil Cammack, one of their young Flight Test Engineers called. I believe Phil is the real driving force in putting these attempts together. “We think a handful of records are already in the bag and there are several others we have an outside chance at landing,” Bob and Phil relate. “The Army pilots at their Edward’s Detachment will fly everything below 10,000’ and we civilians will get the tough stuff above 10,000’ . . . or over ten hours.” Most army helicopter pilots never receive Physiological Training, altitude tank experience in non-pressured atmospheric conditions or instrument training, flying in the clouds. “Three of the marginal records will be Weight Class for Altitude and Unlimited for Distance. Our Jack Zimmerman will be shooting for altitude, Bob will be going for a good wind on Unlimited (All Class) Distance in a Straight Line and you’ll get a try for Unlimited Distance in a Closed Course. Since your flight is in a circle, you’ll get no help from wind. You and Zimmerman will end up at the highest altitudes and have drawn the short straws because you’re the lightweights.”

“Hey, being the 99 pound weakling in High School finally pays big!” I quip . . . and then continue, “I’m honored, men. How can I help?”

“I’ll send you an application package you’ll need to submit for your sporting license,” advised Phil. “FAI is the longstanding agency in Paris that began keeping Aerospace Records with the first balloon flights. They run this thing like a Duck Shoot. You apply for a hunting license through the National Aeronautics Association in Washington DCand we’ll pay a fee for each record you want to challenge. They issue you a passport type license with your picture. Inside are stamps for each record attempt that are good for a certain sanction period, normally ninety days. So for the 90 day period, you will be the only eligible candidate for the record; and of course, we’ll go armed only with the Allison powered YOH-6! Not to dampen your hopes but we only have a few day window, maintenance or weather can scrap any or all of us.”

Bob adds, “Your job will be to just show up Edwards . . . when and IF we can get their SPORT (Spatial Positioning and Orientation Radar Tracking) scheduled. They will track you over the two-day flight for validation, and it’s hard to get priority that long. . . .”

“Not JUST to show up,” Phil jumps in, “But show up programmed in a sleep pattern to depart bright-eyed and bushy-tailed at midnight, targeting lower temperatures for enough lift to get you off at almost TWICE maximum allowable weight. We’ll be in touch,” he concludes. I always had trouble sleeping when contemplating a good fishing trip with the family. This will be no exception.

Go For Gold

I’d flown into Edwards many times in support of rescue or test operations but this is my first trip by ground. The drive from Lancaster reminds me why this location was picked . . . the expansive salt flats give plenty of self-sealing runways; every time it rains the ground cracks fill in, for a natural healing process, giving a relatively smooth landing area for miles.

Reaching Army Flight Ops, I arrive in time to see Army Lt. Col. Richard Heard fly a 3 km course record to set the Light Weight Helicopter Speed Record at 171 mph. This is established by flying a short, level run at maximum speed, turning 180 degrees and returning over the same course with speed measured electronically. Once three round trips are completed, an average of the three runs validates the new record. During the previous week, several other records had been won by the agile helicopter. “If the ship and engine hold together, Jack, your flight will launch at midnight tomorrow night. You’d better hit the pad and get in sleep sync,” advises Test Engineer Phil Camack.

I’d already been getting up at 1 a.m. Indy time,10 p.m.Edwards time but this afternoon I just couldn’t sleep. Phil hands me fresh target altitudes for the different weights to optimize engine power vs. fuel burn for best true airspeed. This matrix, rather than sleep, streams through my mind.

The alarm buzzes at 9 p.m. as I wake from just a few minutes light snooze. I roll onto the base on schedule at 2200 hours, 10 p.m., dressed in a summer flight suit. I pull my flight helmet and oxygen mask from my crew bag and tuck the Sporting License in a leg pocket. Walking to the ramp, the maintenance crews are securing the ship; we are scheduled for liftoff in less than two hours. Suddenly I don’t feel ready. I continue with preflight of the aircraft. If something can be found wrong, maybe we will lose the launch window. “Stop that thinking,” I say to myself. “You know you really are READY for a shot at this record!”

As I finish my checks, it is fueled with pre-cooled JP-5 fuel. JP-5 is a heavier Navy type fuel, effectively No. 1 Diesel Oil. Army/Air Force standard fuel is JP-4, which has a percentage of lighter weight gasoline. The gasoline mix provides better ignition in cold weather. JP-5 or heavier fuels are dictated by the Navy for shipboard safety, but their aircraft generally utilize fuel pre-heaters. The advantage of utilizing JP-5 for this flight is that being heavier; it produces more BTU’s per gallon. By pre-cooling and shrinking the fuel, we squeezed in a few more cups of BTU’s. If this is going to be a win, it will be marginal. As they finish fueling, the fuel is already warming in the tanks, evidenced by expanding vapor exiting vents. The “Egg” looks like a miniature spacecraft silhouetted in the night lights; proportionally, it is.

Getting a final physical check by the Base Flight Surgeon, I ask him for some No-Doz pills. He slips me a box and says, “Take two as needed.” I don’t need them now, I am geared to GO. Just as they close my door, the doctor sticks his head in and asks, “What do you have for a snack?”

“Nothing,” I reply, “We’re going at minimum weight!”

“Try this tube of apple sauce,” he adds, slipping it through my closing door. “We designed it as high energy protein for astronauts on the Apollo Missions.” The ground crew subsequently closes my door and seals it, as are the others, with propeller (duct) tape. This cuts parasite drag and hopefully, will pick up one or two needed knots in speed. While I strap on my parachute, I wonder if I could actually break the tape seals on the door to bailout if the ship became a falling coffin.

A final cross-check of fuel and oxygen shows all systems ready. I give a spool-up signal by rotating an index finger over my head. The crew chief responds likewise, I hit the starter and the engine is on its way. After a short one minute run up, I began to lift the ship off its skids into a hover by raising the collective pitch lever in my left hand. The main rotor blades take a proportionately bigger bite of air and the engine responds automatically to increase power to maintain rotor rpm . . . but we are too heavy and sit there on the skids. I look at my buddy in the left seat; they’d painted a smiley face on the black fuel bladder fixed in the seat straps. “You and your brother in the back are just too heavy”, I think. “Maybe we shouldn’t have pre-cooled your fuel!” They had built a full ceiling-to-floor, form-fitting fuel tank for the back seats. It too, is full.

Holding maximum power, I nudge the cyclic stick forward, trading vertical lift for forward thrust; still no movement. I push the cyclic forward to the stops. The vibration of the rotor hitting the stops break the ground friction and we start sliding forward on the sandy concrete. At fifteen knots, clean air over the rotors produces slightly better lift; I can feel the ship getting lighter on its skids scraping along the ground. I neutralize the cyclic and we begin to lift off at 20 knots, barely skimming the ground a few inches.

35 knots, good, I initiate a shallow climb . . . have to get over the first range of hills just a few miles away. With all this fuel, we are set to be a fiery napalm bomb if we hit anything. If something happens to the engine at this weight, there will be no recovery!

Where’s The Hill?

The slow climb is agonizing, we gain only 100’ the first two miles down the runway,. I don’t remember my trig tables, but this has to be less than a two-degree climb angle. The course is 60 kilometers in circumference and in 20 km I have my first range of hills to scale or it will require orbiting a turn or two before proceeding. We can’t afford that luxury. The course is laid out by a set of twelve pylons and if it were daytime, I was told, I’d be able to see the marker on the ground . . . but not tonight. “Army 49213, this is SPORT. We marked your time as you turned from the taxiway down the runway, Good Luck!, we’ll call your turns for you; suggest a 30 degree turn on the first few until we can help you with the winds.”

“SPORT, Army 213. Thanks, I’ll take all the help I can get!” I respond with enthusiasm now that I am on the way.

“213, SPORT, get ready to turn on my mark, 3, 2, 1, turn.” I turn my rough 30 degrees. The runway lights start to drift from immediate view. I am running just a couple hundred feet over the salt beds and need to increase the climb angle. I slowly bled a couple knots off the airspeed with a very slight amount off aft stick. The climb rate almost doubles to 300’ per minute, but not for long . . . finally settles out at 200’ per min. “213, SPORT. Get ready to turn, 3, 2, 1, turn 30 degrees. Suggest you come back left 3 degrees.”

“OK, thanks, SPORT, 213.” I am now staring into BLACK desert and must force myself to raw instrument flight this close to the terrain. As I leave the dry lake bed, I know the hills will be rolling upward. On the next turn I lose sight of all land lights, even in peripheral vision. “213, you are drifting inside the next marker, make an IMMEDIATE LEFT TURN or you’ll cut the corner!” calls SPORT.

“Turning, SPORT, 213,” I turn 90 degrees . . . and I know that doesn’t help altitude. “Where’s the hill, SPORT?” no answer, then . . .

“213, this is SPORT . . . you just cleared it by 80 feet.”

“Thanks a lot,” I think to myself. They always say a miss is as good as a mile. This banter continues for a couple of laps until I settle in and they become accustomed to my turn rates . . . and the ship has enough air underneath to comfortably clear all obstacles. These first two laps take almost an hour each. As fuel burns off, airspeed increases to a couple of laps/hour. In a high speed aircraft, I imagine they just hold the ship in a light bank, clipping the pylons; in reality, they have much bigger courses for the fast guys.

As weight decreases with fuel burn and speed increases, Engineer Phil instructs a climb to optimize fuel burn and engine performance. To determine the best airspeed at altitude, I momentarily accelerate above Vne (Velocity Never to Exceed) for that altitude until I hit Vr, (Velocity of Main Rotor Roughness) and then back off 1-knot airspeed. This gives us the least amount of drag for speed in the rotor system without slipping into retreating blade stall. Fuel management is simplistic. The rear tank filling the entire aft passenger compartment, gravity feeds into the lower main tank. They had installed a hand wobble pump next to my left arm for me to pump out my bladder tank strapped in the copilot seat. Right now I need him full for proper fore/aft balance.

Four hours into the flight and I’m already climbing through 10,000’. To keep my night vision crisp, I strap on my oxygen mask swinging from my left helmet strap. It’s6 a.m.Turning Eastbound, the faint rays of morning appear. It is going to be a glorious sunrise. “A good time for a cup of coffee”, I relish to myself. No coffee but I do have that box of caffeine No-Doze pills. I pull them out of my chest zipper pocket, drop my oxygen mask to a side strap, chew and swallow two of them with a sip from a small thermos of water.

I remember the tube of applesauce. It is still tucked under the copilots fuel tank restraints, kind of tucked in his left armpit. I unscrew the cap and slowly squeezed down a family-size tube of breakfast. Not too bad, at least it doesn’t flow all over the space capsule in a weightless environment; it heads right for the stomach. Kicking back and relaxing, now fully off instruments, I enjoy looking around. I even find five of the twelve ground pylons! At fourteen thousand feet it is time to buckle on the oxygen mask. The air is getting thin. I have at least another ten hours to go, time to get rid of some fuel up front. A little exercise on the hand pump mounted between the seats empties the buddy bag. His painted smile sags to a frown; that is good. He is empty.

“Army 213, this is SPORT. Good morning, sir. The airspace is yours; you are cleared as able to Flight Level 190.”

World Record Attempt

“Army 213, Army 213, this is SPORT, do you read?” I faintly hear the controller call. “You just cut inside that last pylon, enter an immediate left turn 270 degrees . . . or you will blow the mission!” I hesitate to respond, hadn’t slept for over two days. I’m exhausted. Reluctantly, I slowly roll the ship into a lazy left bank. The forces on the cyclic control stick at these altitudes are so heavy that I wrapped an elastic bungee cord around it; fastening ends of the cord between doorframes, to help relieve the flight control steering pressures. This reduced some of the left lateral force but I hadn’t taken another wrap on the cord since passing 20,000 feet over an hour ago. Fatigue is setting in.

Juggling the cord to take up another winding, I slump slightly forward and Howard Hughes’ experimental helicopter slips higher in speed; it only takes another two knots to enter high-speed rotor stall. The violent shaking rattles me back to a minor threshold of alertness. I neutralize the controls and allow the speed and angle of bank to drop back within a safe flight envelope. Terminal rotor stall will flip the craft inverted . . . and at this altitude with little, if any, expectation of recovery. Once upside down, bailout through the rotors is not an option; the only hope is to be thrown clear if the aircraft explosively separates.

“Continue the turn!” yells SPORT, forgetting the formality of radio call signs . . . they know I am hurting. “You’ve got thirty-five degrees to go yet.” I apply a shallow bank to the left. “We’ll call your rollout assuming you hold a constant rate of turn . . . good we see you turning. Get ready to roll level on the count . . . three, two, one rollout!”

I struggle through the next three laps of the sixty kilometer speed course, in the Army’s attempt to capture the Unlimited Class World Helicopter Distance Record for theUnited States.

“Mr. Schweibold! Listen up!” the flight surgeon calls curtly to get my attention. I know his voice. He had called several times before, but now I can sense his growing concern. “Check your oxygen supply again.”

“It’s still half full and turned to Emergency, 100% safety flow,” I respond. I’d been flying fighters and bombers for years, pressurized and un-pressurized, trained in altitude tanks, the works . . . physiological altitude equations were nothing new, but I still can’t analyze what is going wrong.

“How are your nails?” he replies on queue.

I pull my left glove off and stare through a fogging visor to inspect my finger tips, “Rosy red!” I say softly, hoping for some other reassuring direction. Silence, he is still looking for some sign of hypoxia that might be contributing to my exhaustion. “How about taking a couple of those No-doze capsules I gave you?” he finally adds.

“Took several over the past few hours,” I admit, to turn off his interrogation. Don’t want to tell him I had already choked down the whole box of twenty-four tablets hours ago, lack of caffeine is not the problem.

“Can you hold on for two more laps?” the Engineering Project Manager asks comely, “It might be best to bring you in now. You’ve already set the Light Weight Class Record.” However, I understand nobody really wants an early termination. Months and years of effort have gone into designing and building this ship . . . but half-a-pie might be better than none at all.

Air is leaking from my mask; I reach up and pull the mask straps tighter with my still naked but now cold hand . . . leakage stops as the mask seals in raw crevices of cheek. Two more laps feel marginal and fuel is already bumping on empty. Softly I reply, “We’re, we’re . . . going for it”. I can only listen now, no vocal resource left. I can’t understand, four miles high, but I’m drowning. . . .

The Final Lap

Someone seems to be talking through a watery mist . . . “This is the Final Lap, Jack . . . hang in there!” called Phil. Phil sits with a secondary microphone in the control center and can transmit to me on a separate receiver in the ship. Everything seems to be happening in slow motion. I don’t really think I can “hang in there”.

In fact, I can “Hang” no longer. Suddenly, to my immediate front right side, I see a white robed arm slowly uncoil out of the dark violet sky and open its hand toward my door. I move to eject my door and step into it. His voice is low and astonishing, “No, not yet,” the hand and arm slowly retract and disappear. This gets my FULL attention. I yank my oxygen mask off, at 22,000’, I don’t care anymore. If I’m going to die, I’m not going to be strangled by the mask!

“Army 213, turn 30 degrees on my mark . . . 3, 2, 1.” As I struggle to make the turn I experience a rush of energy . . . but turning, I’m staring at a giant thundercloud forming. It towers thousands of feet above; it drifted into my track since the last semi-conscience circuit. I can’t fly through it at these altitudes, especially in my state of alertness and its internal turbulence. I’ll just make a wide turn around it. With only a handful of gallons remaining, I have to chance the detour. I turn back left twenty degrees. Skirting it, it just keeps growing bigger in height and girth, like an ugly Genie expanding out of its bottle!

“Army 213, we’ve lost radar contact with you. Reply please!” SPORT called. They couldn’t hide it any longer, now I could sense in them the concern I’d felt for the past few hours.

“SPORT, 213, I’ve turned left to go behind this thunderhead in front of me, can’t fly through it and don’t want to clip inside a pylon now. 213 is descending out of Flight Level 210.”

“Army 213, reply; we’ve lost contact with you!” SPORT continued several times and . . . even they fade out. At 19,000’ and several miles outside my course . . . I’m feeling GREAT . . . even without my oxygen mask! I should be unconscious by now. I recheck my nails, still good and red . . . plenty of oxygen. I’ve been unconscious before at 18,000’ without supplemental O2. What’s going on?

Once through 16,000’ I turn back and parallel my last course assignment as I tuck under the cotton candy swirls of moisture forming around the cavernous cloud. Continuing to turn as the fringes of the churning caldron permit, I clear its base at 4,000’ and make a call to delight all. “Sport, 213, clear of the cloud a half mile outside the final marker!”

“Roger, 213, we’ve got you in radar contact again. We must have lost you behind that thundercloud. Good to have you back; we thought you were GONE!” I drop the nose for maximum speed on the remaining descent and will hold it to the finish line. Less than a quarter mile to go now, it’s good to be only a couple feet over the runway again!

“Jack, PULL UP, PULL UP!” Phil shrieks over the secondary radio. “You’ve GOT to finish HIGHER that you started!” I immediately pull aft cyclic and zoom UP several hundred feet and cross the Finish line.

I make a high speed turn and head for the ramp. The crew is waiting and waving. It has been a long night for all. As I land the ship, it is hard to wait out the 60-second cool down requirement. I hope it will just use its last fumes and run out of fuel. The engine stops, I lock the controls, unbuckle my chute and hop out; in fact, I keep hopping for several hours. Twenty-four No-Doz pills have me running at full throttle . . .

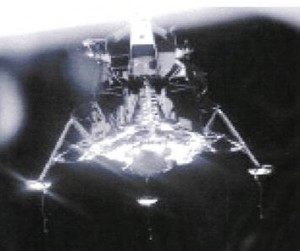

Years later, in looking back, besides setting the World Unlimited Class Helicopter Closed Course Distance Record at 1700 statute miles, one that still stands today; I had tested a new element of aviation . . . the food tube. On the flight Surgeon’s examination of my oxygen mask, still hanging from one strap on my helmet, and the applesauce tube, we found a major structural failure had occurred in flight. While pumping applesauce into my mouth, it squirted out one end of its ruptured seam into my hanging oxygen mask, sealing both EXHALATION ports while I enjoyed the morning sunrise. At the lower elevations I didn’t notice the blockage. At higher altitudes where supplemental oxygen pressure automatically kicks in, I had perceived the problem as mask leakage and tightened the straps. Well, it WAS leaking. It couldn’t hold the pressure, and I just kept exhaling HARDER against the pressure. In all, it was easy to suck in but . . . but like blowing against a sealed hand forced over your mouth . . . for eight hours. No wonder I was exhausted! When I took my mask off at 22,000’, it didn’t matter; my blood was so oxygenated I probably could have stayed alert quite awhile! Hopefully, the Flight Surgeon could secure a design change before our Apollo astronauts headed on a much longer flight a couple of weeks later … to the moon.

As for the arm, hand and voice; I never said anything for years or hung my salvation on it (that comes the moment we trust only in Christ to take us to heaven) but chalked it off to my pastor’s message that visions were from eating too many hamburgers. However, I am now convinced that my wife and children’s prayers at that very moment had a lot to do with this supernatural rescue. Even if it was a nitrogen narcoses reaction, I’m thankful that my heart and mind tuned to thoughts of Christ; the picture is engraved there . . . of being In the Safety of His Wings.

Award Ceremony

We were on our way to the National Aeronautics Association’s Awards Banquet in Washington DC. The other part of the “we” was Allison’s Director of Public Relations. Suddenly, I needed a babysitter on Trans World Airlines! It took me some time to gauge exactly why he was along. I assumed it was to keep the corporate nose clean and see to it I didn’t insert my foot-in-mouth.

Upon entering the banquet room, I was stripped from his protection and given a seat with others who would receive awards. By chance, I had the opportunity to sit at one of two tables for eight in front of a lustrous head table that included: Vice President Hubert Humphrey, Charles Lindbergh, General Jimmy Stewart and Bob Hope. Oh, they weren’t there for us helicopter jocks. They were there to hear and honor our guest speaker who was also sitting at my table, Col. Neil Armstrong. Neil had just completed a two week quarantine being the first man to set foot on the moon. He would be making his first public appearance since returning to Earth.

This was an outstanding opportunity; Madalyn Murray O’Hair had just badgered the US Supreme Court into throwing prayer out of public schools. Now she was back on her broom, petitioning the court to kick Bible reading out of space. The first Apollo Mission to orbit the Moon occurred last Christmas Eve and found the crew quoting Scripture, “In the beginning, God created Heaven and Earth. . . .” Part of her thesis was supposedly that Neil Armstrong was believed to be one her fellow atheists. Discussion at the table was already lively; I could hardly wait to hear his presentation!

Col. Armstrong described his descent from the Orbiter Vehicle as one continuous series of problems and wasn’t able to look out either of his two side windows until the landing module was righting itself in the automatic mode. “I glanced out and saw giant boulders . . . the size of cars and trucks,” Neil vividly painted. “Realizing I was on the edge of a crater, I elected to utilize my God-given right and take over in the manual mode to hover to a clear area.” (He was obviously a trained helicopter pilot) He continued, “. . . The final seconds fuel exhaustion warning sounded, I don’t know who landed the ship!” Col. Armstrong concluded.

I still don’t know what Neil’s religious beliefs are but that certainly didn’t sound like an atheist to me! I never again heard Madelyn take on NASA; in fact, a few years later, NO one heard from HER.

Copyright 2005/2012 Jack Schweibold, Chapter 15, In the Safety of His Wings

http://www.amazon.com/The-Safety-His-Wings

It's

a pleasure to revisit history once in a while.

Neil

I had the great pleasure and honor in working with Jack on many Soloy projects that used the Allison 250 series engines. Jack knowledge and experience was enormous help to us interesting and worthwhile projects.

Thanks Nick,

You were the Soloy treasure, an extremely talented engineer … the heart of Soloy's success. Thanks for letting us know you are still well. It was a joy to know you….

Jack

What an absolutely riveting story.

I have had the pleasure of meeting three great men. Frank Whittle, Bob Hoover, and you.

Don't know if you remember the Allison Training Center, but the manager Connie Martin, instructors, Bob Cook, Jessie Phillips, and myself all knew we were in the presence of greatness when you visited the training center. Will never forget the times you indoctrinated us to the helicopters, both the OH-6A and the OH-58.

Thanks Jack for the article and the memories . God Bless.

Larry Ritchey